A day trip out of Chengdu city – Qingcheng Houshan 青城后山

August 11, 2018

The morning light had just become strong enough to see.

Lying in anticipation of the alarm clock, I resisted the urge to spring out of bed. The rest of the house was still silent. I lay reflecting on pictures of the mountain walk at Qingchen Houshan I’d seen online the night before. Images of forest trails, waterfalls, trees trees and trees, the odd pagoda nestled into the forest at strategic vantage points to make the most of the magnificent scenery … I was looking forward to getting there.

One by one, family members joined the morning ritual of breakfast around the living room table in Chengdu. We would wait for my niece to make contact before setting off. We planned to be on the road by 8:30.

(Is it a young person thing? To be unaware of time? or am I becoming a grumpy old man …? My grumpiness was about to be challenged.)

By 9:30 we were finally departing the fuel stop. It seems half of Chengdu had the same idea: fill up their cars for a Saturday drive out somewhere onto the West Sichuan Plain 川西坝子 that surrounds the city.

At that fuel stop in Shuangliu 双流, suburban Chengdu, I didn’t realise that the bowser traffic jam was foregrounding my day.

As the morning wore on it seemed, surely, every car in Chengdu was on the road. Leaving the city’s gridlocked ringroad, I knew most of these cars weren’t headed our way because they kept going on the highway to congest some of the numerous other ancient towns and scenic spots around this part of Sichuan. Alas, enough of them were so that the traffic all the way to our destination was nonetheless … challenging. (more on traffic and driving in China in another post)

Four and a half hours later, after travelling barely 100 kms, we were out of the car and seated at the round table of our late lunch. (late by Chinese standards: anything after 12:00 midday is almost criminal)

Needless to say, my visions of climbing through the mountain forest, stopping to admire clear streams of water cascading through the mountain’s creases, breathing the welcome oxygen of trees, enjoying the symphony of cicadas in the summer heat … these images faded with the hours stuck in traffic at every stage of the journey. The ‘early’ start which was to enable time in the mountain park evaporated a little more with every stop. The continuous stopping and starting diminished my enjoyment of what in fact (see the pictures below) should have been very enjoyable. Another time, I’m sure it will be.

Qingcheng Houshan 青城后山 is a wonderful place. It took me a good meal and about an hour after, to begin to enjoy the fact that this valley in the mountains was indeed beautiful. Despite the hundreds of cars now parked in the sunny three storey carpark, the continous flow of traffic into the valley, and the continous flow of people out of those cars … the scenery and the air, were marvellous.

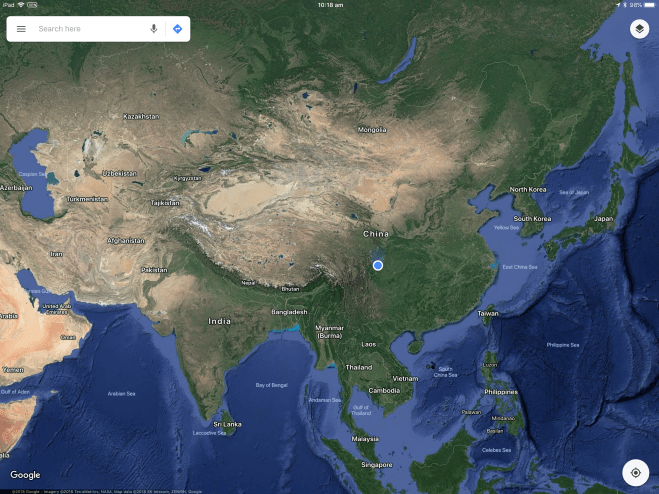

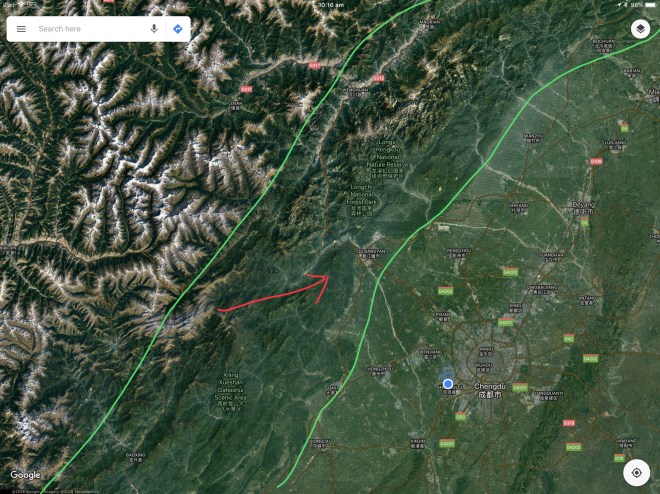

Situated to the northwest just out of Chengdu’s urban sprawl, our destination is just one of the mountains which rise here and continue westward, ever higher, until they roll out onto the Tibetan Plateau.

This means that the water flowing, basically west to east from these mountains, is crisp and clean. The mountainous nature of this enourmous region between central Sichuan and Tibet, has also made urbanisation there impossible. Chengdu is thus the last industrial urban sprawl heading westward before reaching Tibet. The forests in these mountains are healthy, unlike so much of the natural environment to the east which has seen much greater transformation over the centuries from population pressure.

The road west into Qingcheng Houshan follows one of the streams heading east from these mountains. North and south for hundreds of kilometers the Sichuan Basin gives way to mountains like this. About 7 years ago, on my first trip into these mountains we travelled a little further north and followed a river back out onto the Sichuan plain, to the nearby Dujiang Yan都江堰, which is a UNESCO World Heritage site.

(more on Dujiang Yan later. You can read some interesting background on Wikipedia, although there are conflicting and some erroneous details there, it does give a good introduction to the amazing background of this area and why UNESCO classified it.)

The beautiful clean water flowing through this valley today is part of a much bigger picture which has profound historical significance for Sichuan. The engineering project at nearby Dujiang Yan, constructed around 220 BC, was able to utilise the enormous amount of water flowing out of the western mountains to turn the Sichuan Basin into the most productive land in Ancient China. This led to it being, for centuries, the most populous province in the country.

The most powerful memory I have of that first trip to Dujiang Yan, is not the almost unbelievable scale of the engineering feat not only considering the time of its completion but even by modern standards. My most vivid memory is of the clarity and volume of the water flowing there. Its icy blue-green colour seemed to carry the crisp alpine promise of the highlands: the thunderous roar of its rumbling through the levy system that is Dujiang Yan, invigorated everything nearby.

The same water tumbles over the rocks through this little valley at Qingcheng Houshan. The mountain forests nearby are reminiscent of the rainforests of southern Queensland and northern New South Wales. Although the flora is noticably different, the ecosystems have more in common than in how they differ. Walking trails here pass waterfalls and grottoes showing that people here have loved and indeed celebrated the power of nature over the centuries. I hope to have my own photos of this from my next visit.

Although this trip was somewhat tainted by the traffic and crowds, I vowed to return early next year. It won’t be on a summer weekend, and we will stay at least overnight. We ate lunch at a small guesthouse where we discovered we could stay for Au$30 per person, including 3 meals (Monday – Thursday, $40 on weekends).

Even so, it was pleasant to be in an environment that showed not all of the amazing land in China has suffered urban decimation. The abundant trees and constant flow of crisp, clean water was enough to lift the spirits sufficiently to be willing once more, to get into the car.

The road home was almost all downhill – it only took 3 hours to drive the 130 kms back to Chengdu’s outskirts. It was just dark when we arrived, hungry and tired. Fortunately, there are lots of food options nearby in any Chinese city. Being in Chengdu of course, we chose hotpot. Just a five minute walk from home is the West Sichuan Plain 川西坝子hot pot restaurant.

Chongqing to Chengdu

August 06, 2018

On the train from Shapingba in Chongqing to Chengdu. The journey is just over one and a half hours by high-speed rail. The seats are comfortable, about the same as airplane seats but with more leg room. The carriage is smoothly quiet considering we’re travelling at over 160 kph and it’s full of people. Large windows line both sides of the carriage from about seated elbow height rising just over a metre and about two metres long: great views of the countryside sliding by.

The train traverses the Sichuan Basin, the middle of Sichuan Province between Chongqing and Chengdu. From start to finish we’re crossing rolling hills about 20 to 50 metres high, littered with small valleys and dotted with rustic Chinese farmhouses. Some of these are clustered into small villages, but many of the houses are relatively isolated, surrounded by their cropland. There is no monoculture: all plots are small, averaging about 30 – 50 sq. mtrs. They form a patchwork of different plants at different stages of growth. There’s quite a lot of corn, but most of the rest seems to be a variety of vegetables. There’s a lot of water; dams or small rivers are almost never out of sight somewhere close by. The land looks rich and almost every piece of easily arable land is producing something. Where the land isn’t cropped it is covered by trees so that the overall impression is green, almost lush. It’s a very pleasant landscape which makes the smooth, air-conditioned comfort of the ride even more relaxing.

There are several small cities along the way which are characterised by their new railway stations and small collection of new high-rise apartment buildings. These are ubiquitous across Sichuan and Chongqing. They all seem to be roughly the same: about 30 storeys high, housing approximately 7 units per floor of various configurations. They’re oddly impressive simply by virtue of their presence. They’re all new and always clustered close together: a stark contrast to the countryside surrounding them.

As we get closer to Chengdu mountains can be glimpsed in the distance, marking the foothills which rise to the Tibetan Plateau. They have disappeared in the haze of the city as we begin our slow down approach. Urban Chengdu rises in the white grey haze marked by ever larger clusters of high-rises until there seems to be nothing but them.

We pass a cluster of three smaller groups, each identifiable by small differences in their design. They all occupy the same amount of earth and rise about 30 storeys, just like thousands of others, many of which you can see in Chongqing. I counted 36 buildings in total in this development alone. Think about this for a moment: 36 buildings, each 30 storeys, each storey containing the homes of about 7 families: that’s 7,650 apartments. There are countless groups of buildings like this clustered all over the urban sprawl of modern Chengdu, but also replicated to some extent in every city in China.

Chongqing, the beginning of this short journey, is very hilly throughout. The urbanisation there is forced to follow the lay of the land as two large river valleys converge where the original, much older city is built. Chengdu to the west, is dead flat. Like some other famous cities in China which have grown around their ancient origins, Chengdu is laid out in a geometrically organised grid. It is one of the oldest cities in China and was the capital of the southwestern third of the country just after the peak of the Roman Empire in the first century AD.

In 221 BC Qin Shihuang had overcome the various warring kingdoms of the time and unified them all in a very short but historically important dynasty. This is accepted by the Chinese as the beginning of the country we call China, as the core of this unified territory has maintained an identity as a unified country since then. The Qin Dynasty only lasted about 20 years but its legacy of unification was taken on by the Han Dynasty which lasted much longer. It is from this era of Chinese history that the dominant cultural group in the country take their name: Han Chinese make up 95% of Modern China. This is an ethnic group based on cultural history which contains people from many different genetic backgrounds who have been mixing genes for the past 5000 years at least. Other ethnic groups in China are more clearly defined by genetic as well as cultural norms and make up the remaining 5% of the population.

As the Han Dynasty was fighting for its survival, late in the second century AD, three rivals were fighting for the right to rule the country. One of these, Liu Bei, claimed to be the rightful heir of the Han Dynasty and fought to restore it. His capital was Chengdu. Although it has obviously changed enormously since then, it has grown around the original city of that era. It is one of the oldest continuous cities in China.

One of the endearing aspects of Chengdu is its ancient heritage dating back almost 2000 years. The Sichuan Basin and the foothills of the Himalayan Plateau, which also form part of modern Sichuan Province, are littered with small ancient towns, many of which have been restored as tourist destinations. Unlike the garish kitsch of so many tourist destinations in China, many of these ancient towns have been well-managed and faithfully restored. It is very easy to get to many of these within two hours drive of Chengdu. The city itself has many famous remnants of its ancient heritage.